These essays are meant to be provocative, based on a red team principle, jester’s privilege, and my love of the Oyster Club. It is my aim to stress test Westminster concepts, learn from the feedback I receive, and introduce new ideas occasionally. I try and write them in a conversational manner.

I am a firm believer in putting pen to paper, or fingers to touchpad, as a means of refining thinking. I will certainly get things wrong, but that's how I learn. I do not have all the answers for the questions I pose in my writing.

These views are mine and mine only: they do not represent my employers.

Hello,

Conversations in British politics are cyclical and seldom well-informed; one topic that surfaces seasonally involves the supposed harm that "anonymous" Twitter accounts inflict upon Westminster. Such debates are typically conducted with more heat than light.

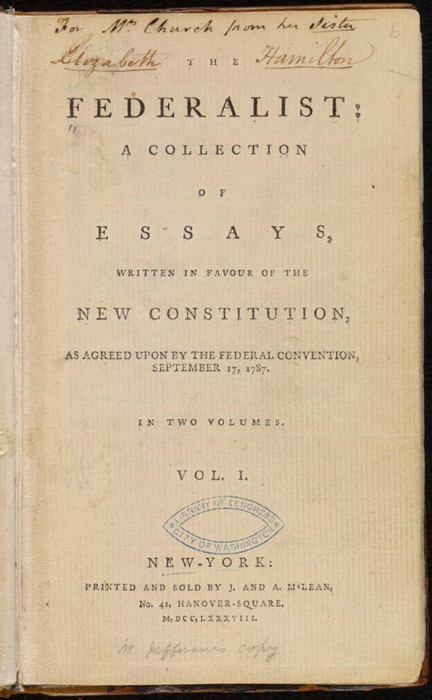

As someone who built a company anonymously for 18 months, and who has observed Westminster from various vantage points, I want to position that anonymity serves a vital function in British political discourse. I subscribe strongly to the argument laid out in what The Economist has termed the journey from "posting to policy," with relation to Twitter/X.

I propose one strained metaphor and two short experiments on the matter. Let’s have some fun!

—

The Westminster Exchange

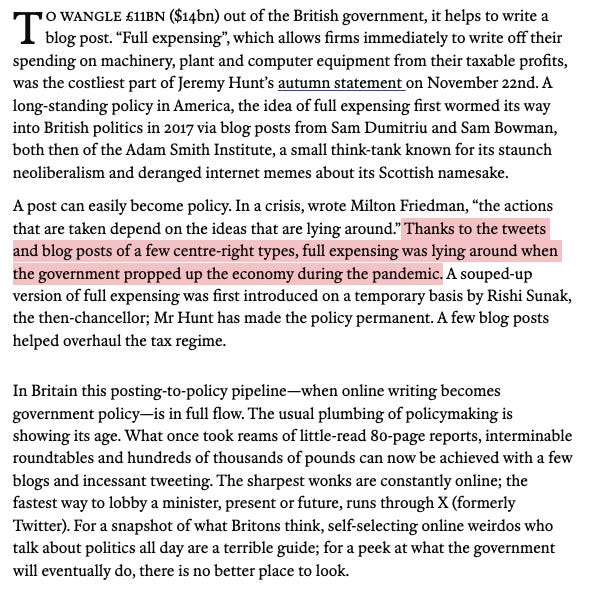

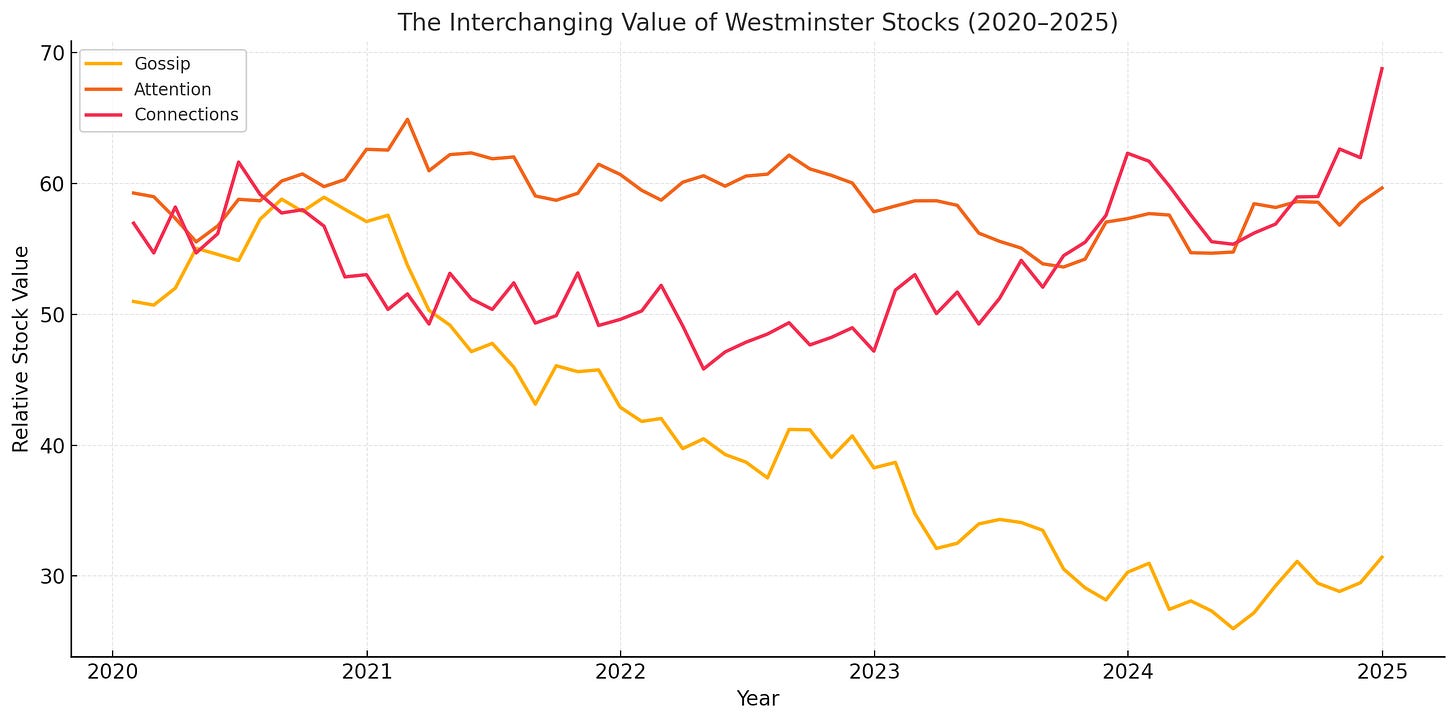

Imagine, if you will, that Westminster operates as a stock exchange. The three most valuable stocks traded are Gossip, Attention and Connections. Let us call them GAC. Market participants - MPs, special advisers, think-tankers, journalists and hangers on - buy and sell these equities according to their perception of what will boost their own portfolios.

Watch the market over time and you observe the familiar boom-bust cycles. Gossip soars during a leadership contest, attention enjoys unique peaks around budget season, connections rally whenever reshuffles loom. The big Westminster banks - newspapers, broadcasters, podcasters - once provided reliable sell side reports through their research departments. But their analysis has grown stale, recycling the same threadbare insights with the same people and the with diminishing returns. Additionally, many of them have a vested interest in not sharing certain analyses: their reports still sell just enough to make them profitable.

Meanwhile, one stock remains persistently undervalued: “Original Strategic Analysis”. or OSA. The sort of work that involves actual research, uncomfortable data and conclusions that challenge received wisdom. This intellectual equity barely registers on Westminster's trading floor, crowded out by the relentless demand for GAC.

This is partly because of two driving forces in Westminster:

Patronage: Westminster can resemble a club more than a meritocracy. Career progression can often depend on who you know and whom you offend. Challenge the wrong person's pet theory at the wrong moment and you may find yourself excluded from the next reshuffle, policy review or lucrative consultancy gig. Journalists face the same pressure: annoy a press chief and the flow of briefings soon stops. All of this makes people think twice.

Social capital: There is a sometimes a social cost to being first with OSA. If your view clashes with polite dinner table chat, you risk losing invitations, allies, and short-term credibility. Most people wait for someone else to stick their neck out, or skip the debate altogether, so safe opinions usually win by default and OSA is ranked lower.

—

Speaking Without Fear or Favour

Consider a thought experiment.

Twice a year, every British MP would quietly receive three to five anonymous policy papers, each capped at 2,000 words, each written by one of their MP colleagues. Each is an assessment of the challenges facing Britain, complete with specific policy recommendations and suggested, data-filled trade offs.

For every paper the MP must award three separate 1–7 scores, covering evidence strength, practical feasibility, and honesty about costs, then add a brief note (no more than 150 words) quoting at least one fact or figure from the paper.

When the six month window closes, the briefs are ranked by their median scores, with a penalty for wide disagreement and a small bonus where MPs’ comments show real engagement with the data. Every vote carries the same weight.

The public sees the top and bottom scoring 10 briefs, simple charts of medians and spreads, and twice yearly notes on any attempted manipulation; authors may choose to disclose their names after two years.

What might these politicians write if liberated from the constraints of party loyalty, constituency pressure and career advancement? The gap between their public rhetoric and private thoughts would likely prove illuminating. And that’s before we consider ways that AI systems could enhance this process [imagine a personalised learning loop for MPs, where GPT-5 clusters peer comments on their briefs, highlights repeated weaknesses (“source outdated labour-market series”) and suggests targeted reading lists.]

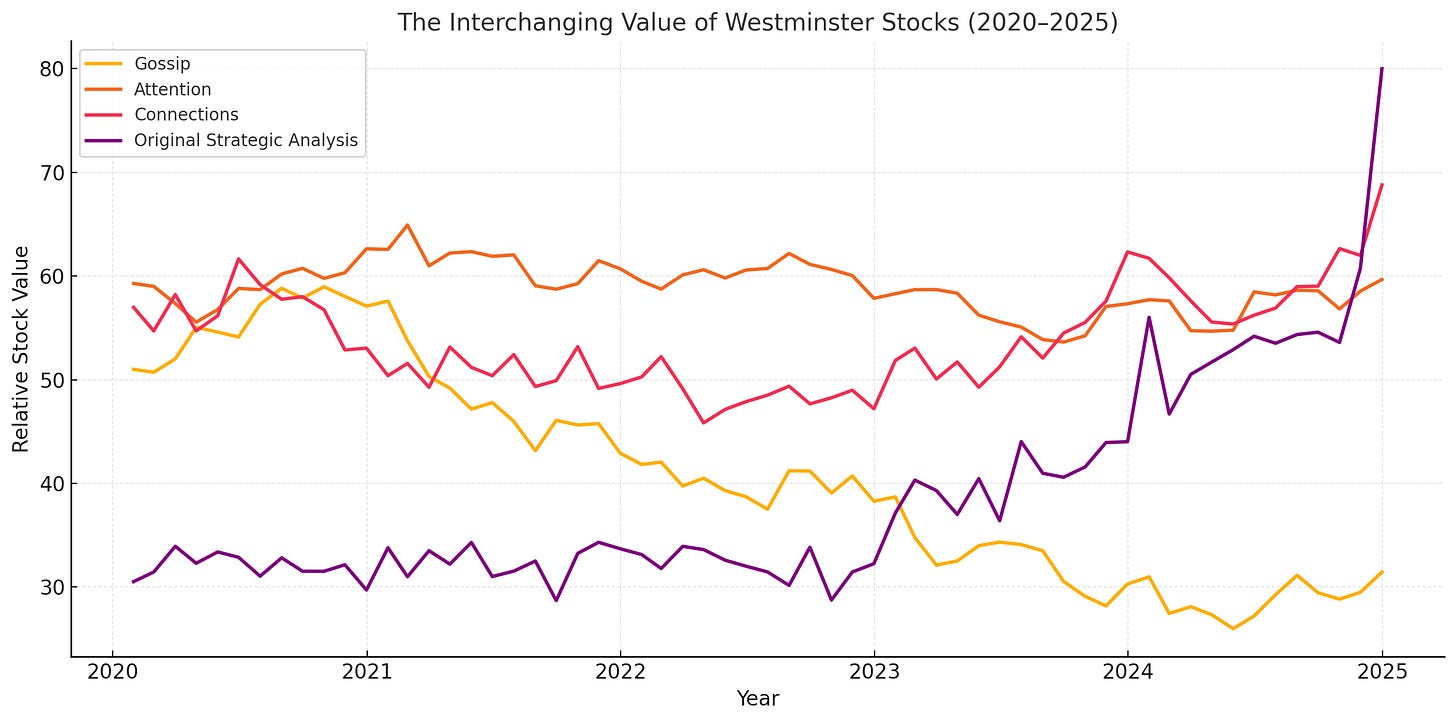

The Federalist Papers perhaps offers the strongest historical precedent for this sort of anonymous policy-based writing. Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote anonymously as "Publius" to avoid personal political consequences while making substantive arguments on the ratifying the constitution. Clearly they ended up revealing themselves, but pushed clear and reasoned arguments forward prior.

—

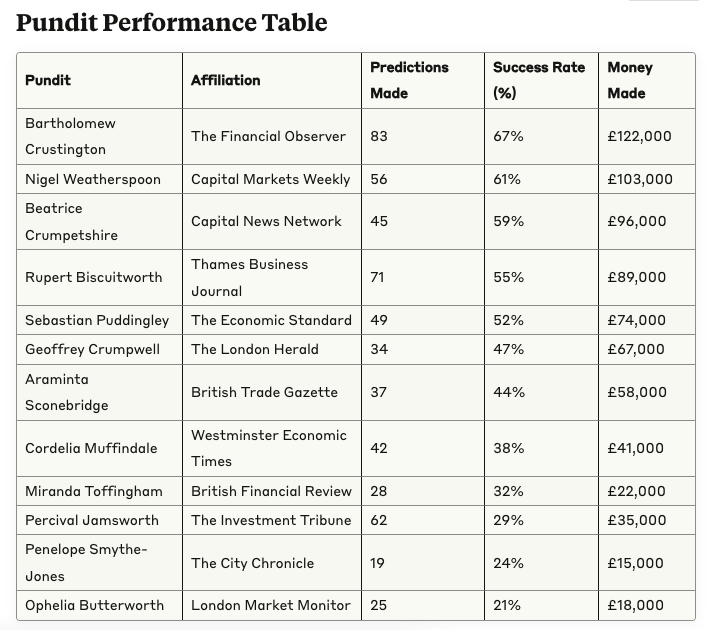

Pundit League Table

Let us consider a second experiment. Every time a political pundit makes a prediction on paper, television, or podcast, they must make a bet alongside it. If their prediction comes true, they win. If not, they lose. Pundits are measured on a real time table that shows the total number of predictions/successes that year.

Now consider this again if it was run completely anonymously. It’s a stimulating prospect, because while open to manipulation - Anon Journo 2 bets MP Y will resign by next week, having just shared a boozy lunch with them - it might lead to some new outcomes. Do anonymous accounts take more contrarian positions?

—

To Conclude

Group think is dangerous, and most people are susceptible to social pressure at the best of times. In politics, there are many incentives that work against the introduction of ideas and concepts that challenge the Current View. To this end, anonymity can insert original or new angles into the debate without losing social capital in a way that many in Westminster cannot or will not.